"It's different, but it's very pretty out here."

One night when I was six years old I was standing on the front porch with my father, we were both looking up at the moon. I should mention that this wasn't that boring sterile rock of a moon that these days rarely gets a moment of my attention. No, this was a brilliantly luminescent sphere that I remember as a kid spending countless evenings staring at with a toy telescope. It was the same moon that one day I knew I would visit.

One night when I was six years old I was standing on the front porch with my father, we were both looking up at the moon. I should mention that this wasn't that boring sterile rock of a moon that these days rarely gets a moment of my attention. No, this was a brilliantly luminescent sphere that I remember as a kid spending countless evenings staring at with a toy telescope. It was the same moon that one day I knew I would visit.

The moon at the time was only about a quarter full but the night was a crystal clear winter's night in July so the crescent was brightly contrasted with the black sky behind it. Dad said: "Right now there are men walking around up there". I knew it too but just the thought of it was simply thrilling. Even at that age I knew that the moon landing was unprecedented, something totally new.

I guess that Apollo program in the end made the moon boring. What looked like the dawn of an exciting new era in space exploration ended up being just a high water mark before the malaise kicked in. No life was found there, just some rocks and then some more rocks. I remember watching the last of the Apollo 17 moon walks in 1972 on a TV set in the local shopping centre. Nobody was standing next to me watching it with me, no one could care less, they just got on with their Christmas shopping. As someone put it recently:

"We went to the moon. We drove a car around on the moon. We played golf on the moon. I think we've done everything practical we can with that useless rock."

Of course in reality they had a whole lot more fun than that! The transcripts of Apollo 11 landing and the moon walks make riveting reading. I mean it, go and immerse yourself, they're are really fascinating and the commentaries fill in the context as well as provide links to images and film clips. Transcripts of the other Apollo moon journals can be found here.

To be honest, I never could get very excited about the Space Shuttle. A space vehicle that could never leave the earth's orbit and was only meant for delivering new satellites or picking up old ones just wasn't space travel in my book. Its aims seemed so mercantile and mundane. It's one key feature, reusability, was something that only an accountant could really love. Instead my interest moved to the unmanned space probe flights which over the past 30 years have radioed back countless amazing pictures of the distant planets and their moons. But a Voyager or a Viking is just a camera tied on to a rocket, it's just not quite the same thing as having real people going out and doing real exploration.

In the three decades since the last person left it never to return, the moon has become remote once more. In a way, it seems more remote now than it ever was even before people started planning to go there.

Has the moon finally lost its power to inspire or is it just momentarily eclipsed? I'm not sure, the latter I hope but don't ask me. My three year old daughter has become a far better authority on the moon that me. She notices it even while it's become largely invisible to me. She knows when it's full and when it's a crescent. She points it out when it rises during the day. To her it's wonderful and interesting beyond measure and she reminds me how jaded I've really become. It is truly wonderful after all and this is definitely a good time for me to start looking up at the night sky once again.

Has the moon finally lost its power to inspire or is it just momentarily eclipsed? I'm not sure, the latter I hope but don't ask me. My three year old daughter has become a far better authority on the moon that me. She notices it even while it's become largely invisible to me. She knows when it's full and when it's a crescent. She points it out when it rises during the day. To her it's wonderful and interesting beyond measure and she reminds me how jaded I've really become. It is truly wonderful after all and this is definitely a good time for me to start looking up at the night sky once again.

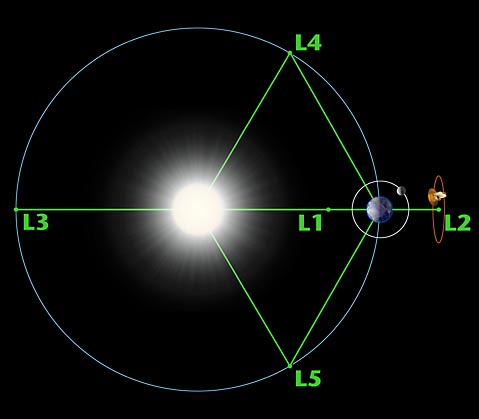

Sometime around April this year, the Earth aquired a new moon. Initially it was thought to be a stray asteroid that had been captured by the Earth's gravity. Now it appears to be the booster stage of a Saturn V rocket, Apollo 12 to be precise, which had been orbiting the sun since 1971. This year it crossed back over the L1 Lagrange point and started orbiting the earth once again. Apollo 12 was launched only four months after Apollo 11 and its return as a piece of space junk is kind of a fitting reminder of those moon flights thirty years ago. It makes me think that it's about time that we went back.

"Right now there are no people walking around up there"

In 1900 a sponge diver called Elias Stadiatos discovered the wreck of an ancient merchant ship off

In 1900 a sponge diver called Elias Stadiatos discovered the wreck of an ancient merchant ship off